saggi e altre riflessioni

Edith Wharton Handwriting Analysis

-ˋˏ ༻❁༺ ˎˊ-

(back to the essay)

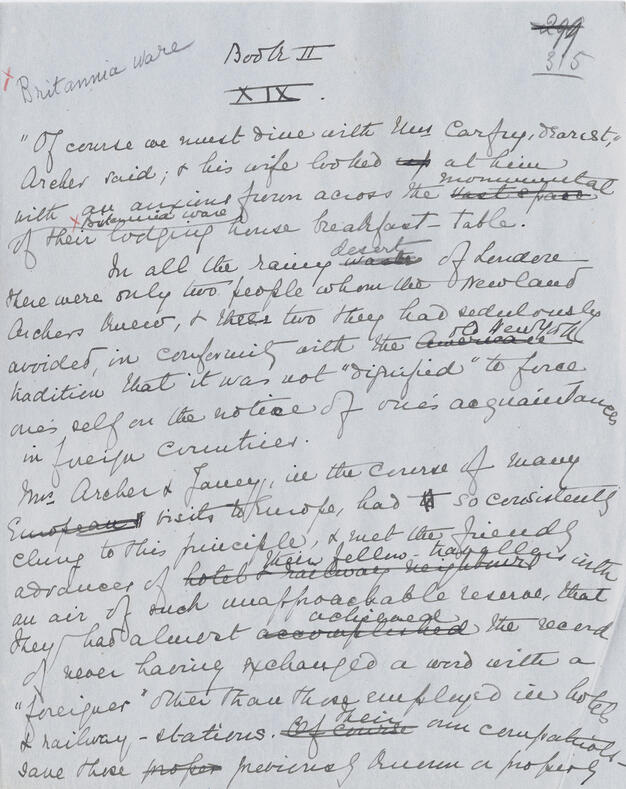

Manuscript of The Age of Innocence

Method: Morettian

Measurement: estimated from pictureWharton’s handwriting shows good practicality, criticality and logic. The caliber is – perhaps unexpectedly – rightly measured and sign of a good sense of the self. She elongated both her upper and lower extensions, which indicates that she was aware and actively mediated with her Id and Super-Ego – but while her Super-Ego is dealt with conscientiously and balancedly, her relations with her Id are a bit more complicated: the lower extensions are overly pronounced, which means that her higher principles could at times be tamed or even overrun by her most immediate instincts and appetites – which would explain very well why in her novels love appears as a purely spiritual quality, in what probably was an effort of reaction against and denial of her truer (instinctual) self.Despite critics signaling her disinterest of others less fortunate, from the reasonable gaps left in between letters we can evince that Wharton was actually very generous and compassionate, unafraid to leave space for others. This is also strengthened by her curve, neither flattened nor pointed: Wharton knew how to communicate with others without losing her sense of the self. The fact that her words rest easily on a straight though unrigid line also demonstrates her ability to sustain delicate psychophysical situations.Wharton was gifted with great logic and analytical skills, as shown by the clear separation of words and lines and by the non-forced fluidity with which she linked and (sometimes) didn’t link the letters.According to the fashion of the time, but also to her own inclination, Wharton’s handwriting leans decisively to the right: this is a sign of a persuasive, possessive person with a romantic nature, that could get jealous very easily and that needed affection – the result of an infancy unsaturated with love and attention (this could also point to her unsteady attitude to love, largely present in her novels). When paired with her aforementioned logical abilities, a right-leaning handwriting could also be a sign of intelligence and of a great vivacity of thought.The extensions also lean ever-so-slightly to the right, showing coherence of thought and action, decisional stability and a comprehensive nature.Though not frequent, the handwriting sometimes disperses itself in useless curls, namely of a subjective and of an ideative kind – meaning that Wharton sometimes had difficulties opening herself up to others as carelessly as she let others open themselves up to her (subjective) and that she also could get unsatisfied with the world that surrounded her, because she would unconsciously compare it to an idealized version of it that she had created in her head (ideative).The handwriting carries speed and is harmonious, which again indicates fastness of thought and an overall steady, lucid personality.

(back to the essay)

Alexandre Dumas Handwriting Analysis

-ˋˏ ༻✮༺ ˎˊ-

(back to the essay)

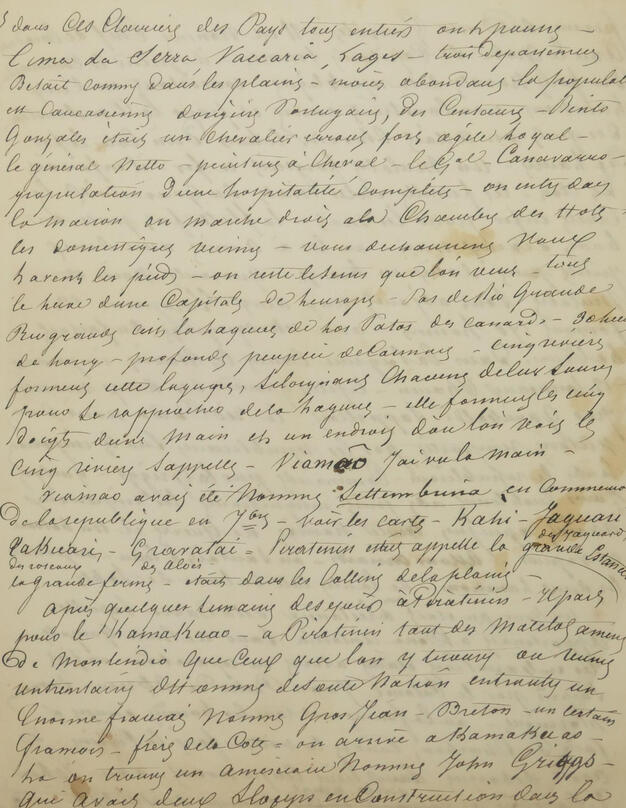

Fragment of autograph Manuscript

Method: Morettian

Measurement: estimated from pictureAlexandre Dumas (father) interestingly had a pretty small caliber: for someone so usually puffed with self-confidence and authority in all of his writings, this does come as a surprise, if one does not take the time to consider that his usual cockiness may have precisely been a reaction against a structural insecurity. Besides, a small caliber is that of an analyst and of an avid researcher, which we know with certainty that Dumas was. The adequate space left between words and the natural and un-anxious linking of letters also point to a developed critical sense and great logic.The extensions, both upper and lower, are present with the right intensity, meaning that Dumas had a pretty balanced and unproblematic relation with the tensions provided by the Id and by the Super-Ego: while they were there, they did not overwhelm the personality and allowed the Ego to govern them both successfully.As far as his relationships with others are concerned, Dumas – though able to leave space for others and despite being moderately generous (the reasonable gap between letters) – could be protective of his own self and be dubious and even dismissive of other people, as signaled by the pointed curve (especially evident in his as and os). The curve also explains Dumas’ verbosity and aggressive nature, typical of an obstinate person that tends to protect itself from the outer world.Dumas rested his words easily on a straight enough imaginary line, mostly horizontal with a slight incline – showing a productive person, entrepreneurial and filled with energy, but also emotionally strong and able to handle delicate situations, even psychologically.Dumas tended to space his words decisively to the right, even avoiding to start new paragraphs and piling words near the right margin of the paper. According to spatial symbolism, this shows a reactive person, oriented towards the future. When paired with a right-leaning writing body, this could also mean that Dumas never healed his traumatic infancy (being deprived of his father very young and immediately be sent to work). Such a right-pending handwriting shows a possessive, manipulative, suasive person: one who can exist socially with ease and who needs attention and who picks things up quickly. This sign strengthens Dumas’ already ascertained intelligence.Dumas’ extensions lean slightly to the left, again pointing to a careful personality, constantly mistrustful and with a tendency to contradict, rather than to adapt. This again seems to confirm what has already been noticed when looking at the sharp curve.Dumas’ handwriting is very laborious, full of curls and other calligraphic embellishments: it is important to remember that he worked as assistant to a notary in his teenagerhood, and that his job was to create facsimiles of important and official documents. Some of that grandiosity must have been retained, but such useless deflections of energy appear maybe even too often: we can easily spot curls of many different kinds, namely some ideative, instinctual and concealing curls. The ideatives show great fantasy and creativity but also a difficulty in accepting the world as it is. The instinctuals (the most present) indicate a lack of confidence in the self (the caliber is, in effect, a small one) and a great economic insecurity (Dumas was always very financially unstable). The concealing curls, lastly, show a tendency to hide and retreat, and could also expose a certain ease in the act of lying.The handwriting is fast and harmonious, which shows a concreteness and an acuity of the self.

(back to the essay)

Jane Austen Handwriting Analysis

-ˋˏ ༻❀༺ ˎˊ-

(back to the essay)

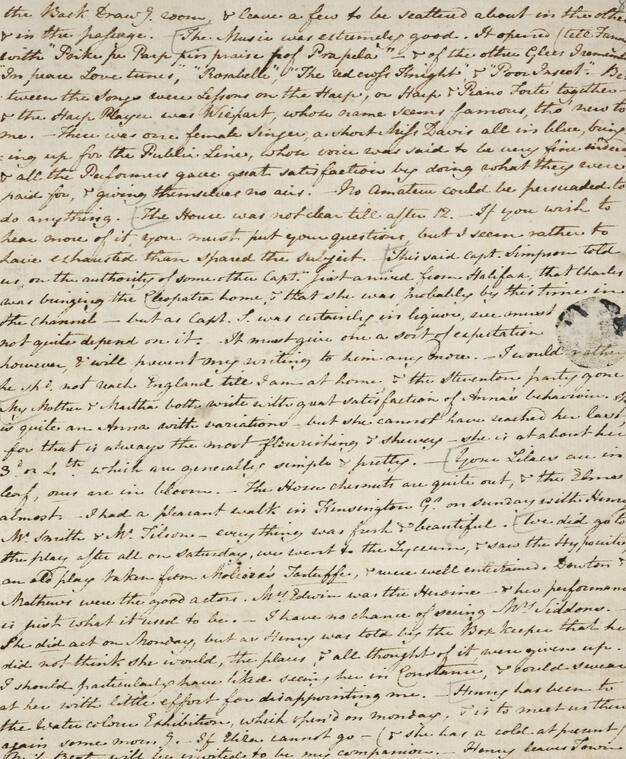

Letter to Cassandra

Method: Morettian

Measurement: estimated from pictureJane Austen’s handwriting is elaborate and delicate, showing a solid though fragile personality. Her caliber is quite small, which is typical of the organizer, of the introvert and of the analyst: people with a small caliber are prone to take up as little space as possible, but they are incredible observers and though usually insecure, they are exigent, selective and profound. A small caliber also usually means a reduced perception of the self.The extensions are clearly present, maybe a bit too excessively: this indicates a rigorous and strong adhesion of the writer to a chosen set of ethical norms, but also a tendency for the Super-Ego to censor – rather than counsel – the subject. That means that while Austen was a very morally-grounded person (which can clearly be evinced by the essentially conventional nature of her novels), she could also be incredibly rigid and unrealistic with her ambitions. Austen’s rigidity is also confirmed by her rather pointed curve, a sign of great acuteness and attentiveness, but also of an obstinate personality that tends to dominate the environment. This would denote little plasticity of thought (people with a pointed curve usually are very opinionated but are not very flexible and seldom change their position) and a difficulty to communicate with others.Despite careful in opening herself up to others, Austen knew how to be generous and leave space for other people – or help them when necessary (the space left between letters shows this perfectly). The limited space left between words, however, might also indicate a slight dependency on family and a lack of autonomy – while it could scarcely mean a complete absence of critical skills and impulsivity, since every symbol is still evidently recognizable and the handwriting is clear and not at all jumbled or confused, and carries speed while maintaining its harmony.The letters are linked almost to an extreme: this indicates a subjective thinking and an excessively formal logic, one which lacks flexibility and tends to rationalize feeling. It is extremely difficult to mediate with these people because they tend to be fixed on their opinions.The words rest easily on a straight but unforced line, which means that Austen was gifted with emotional strength and knew how to handle delicate psycho-physical situations. The lines neither incline nor decline, therefore showing a centered individual and a strong-willed identity.Austen’s handwriting leans decisively to the right, though not excessively: this is a sign of a greatly persuasive, attractive person, with a fluid dialectic and a romantic nature. It also shows a quickness both of thought and in the act of learning and can be a sign of intelligence. The extensions lay predominantly straight, meaning that Austen had a great education (she not only adhered to ethical norms but also to educative ethics) and, though particular, was also coherent and decisionally sound.Austen had nearly no curls, but some subjective ones can be detected in the handwriting: they again indicate a person that avoids physical and affective contact and who tends to protect themselves from the outer world – though being infrequent, they do not constitute a real barrier and still allow contact with other people, though it might be emotionally distant.Austen’s handwriting shows a clever personality, if restrained, but an overly-rigid and uptight moral compass that leads to stiffness and to a closure to the world. Given how constrained it is, we should maybe reconsider contemporary “feminist” readings on Austen and accept her intrinsically poised and conservative values – a reading which is bound to be more fruitful and productive, ideally devoid of ideology and preconceptions.

(back to the essay)

Essays

-ˋˏ ༻✿༺ ˎˊ-